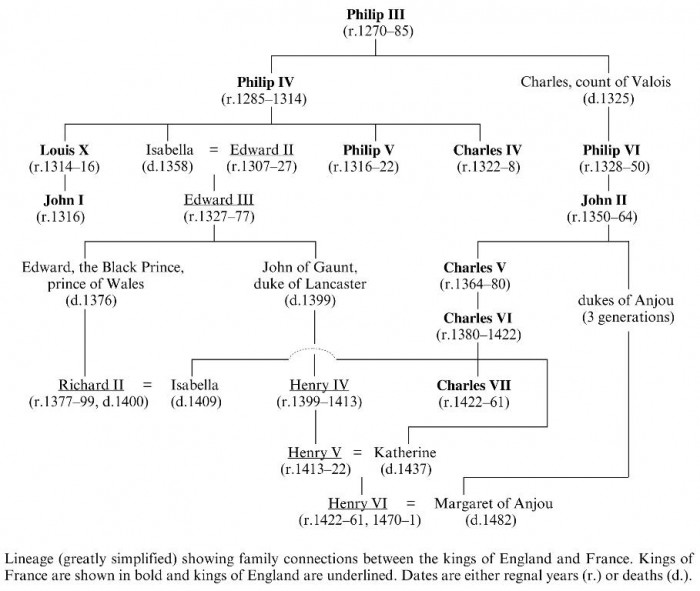

BackgroundDisputes between England and France were not a new development in the fourteenth century. The roots of the uneasy relationship between the rulers of these two realms may be traced back to the Norman conquest, when William, duke of Normandy, became king of England. Ever since that time, English kings held various territories in France, but they held them as dukes or counts, owing homage to the king of France. This relationship, along with the question of the extent of the English holdings, was a frequent source of conflict. The other main cause of the Hundred Years’ War was Edward III’s claim that he himself was the rightful king of France, following the death of King Charles IV without any direct heir. This claim had some foundation, since Edward was Charles’s nephew, but the French nobility preferred to have Charles’s cousin, Philip count of Valois, as their king.

Further factors which drew the two nations towards war were Philip’s support for the Scots in their own conflict against Edward, the cancellation of a proposed crusade, and the differing economic interests of England and France. The Hundred Years’ War was not a period of continuous fighting. It can be divided into several key phases. 1337―1360 The first major battle of the war on French soil was the battle of Crécy in 1346. Edward III’s army won a decisive victory over Philip VI’s much larger force, thanks in large part to their effective use of archers in combination with men-at-arms. Philip fled to Paris, whilst the English went on to besiege and, eventually, capture Calais. Edward the Black Prince, Edward III’s son, had fought bravely and ‘won his spurs’ at Crécy and, ten years later, went on to command his father’s army at the battle of Poitiers. Once again the English were victorious, and succeeded in taking prisoner the French king, John II. This led to the signing of the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. It was agreed that the French would pay a ransom for their king and concede to Edward III full sovereignty over Aquitaine and other territories including Ponthieu and Calais, in return for which he would renounce his claim upon the French Crown. 1369―1396 The peace established in 1360 came to an end in 1369, thanks to a dispute over the tax imposed by the Black Prince on Gascony in an attempt to recover the costs of his army’s involvement in the war of succession in Castile, northern Spain. Appeals were made to the new king of France, Charles V, who agreed to intervene. On the grounds that the Treaty of Brétigny had been violated, Edward III reinstated his claim to the throne of France, and war soon broke out again. The French recaptured much of the English-held territory, particularly in the period up to 1377. A 28-year truce was agreed in 1396, by which time Richard II was king of England and Charles VI king of France. Richard II married Charles’s daughter, Isabella, as part of this agreement. 1399―1422 Richard II was deposed in 1399 by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke, son of John of Gaunt, who became King Henry IV. The French refused to recognize Henry as king and sent aid both to the Scots and to the Welsh, led by Owain Glyndŵr. In turn, the English raided the coast of Normandy. By 1410 there was civil war in France, the king, Charles VI, having suffered from bouts of mental illness since 1393. Henry V succeeded his father as king of England in 1413. The following year he sent an embassy to France agreeing to drop his claim to the French Crown in return for sovereignty over extensive lands in France, the arrears still owing from the ransom of John II and the hand in marriage of Charles VI’s daughter, Katherine, along with a dowry. The French were unwilling to meet his terms in full and in 1415 Henry sent another embassy with reduced demands. However, the French, now in a stronger position since their own civil war had abated, were now prepared to offer even less than before. Henry V raised a large army, which landed in Normandy in August 1415. He captured the town of Harfleur after a six-week siege then, on 25 October in the same year, met and defeated a much larger French army at Agincourt. By 1419 Henry had taken all of Normandy. In September that year, the two opposing French factions, led by the Dauphin and by John, duke of Burgundy, met in order to try to unite against the English threat. However, a quarrel developed and John was killed by a member of the Dauphin’s entourage. In response, John’s son and successor, Philip, sided with Henry V against the Dauphin, and this alliance with the Burgundians greatly strengthened Henry’s cause. In the following year the Treaty of Troyes made him heir to the throne of France. It was also agreed that he would act as regent until the death of Charles VI and marry his daughter Katherine. 1422―1453 Henry V died two years later, in 1422, leaving a nine-month-old son who immediately became King Henry VI of England and heir to the throne of France. When Charles VI died less than two months later Henry VI became king of France as well, according to the terms of the Treaty of Troyes. But even before Charles’s death large areas of France had remained loyal to the Dauphin, and the English had to continue to fight in order to enforce Henry’s claim. They did so at first with considerable success, led by the young king’s uncle John, duke of Bedford, who acted as his regent in France. A particularly significant victory was won at Verneuil on 17 August 1424, a battle in which Matthew Gough and Sir Richard Gethin, took part. Attacks were launched into Maine and garrisons established there. In 1428 the English besieged the city of Orléans. The Dauphin sent a relieving army led by Joan of Arc, a peasant girl from Lorraine who claimed she had been sent by God to raise the siege. They were successful, and this victory led to others. In 1429 the Dauphin was crowned as King Charles VII at Reims, but Joan was captured the following year. She was put on trial, condemned as a heretic and burned at Rouen on 30 May 1431. The same year, in December, Henry VI was crowned king of France in Paris, though his uncle, the duke of Bedford, would continue to act as governor general until his death in September 1435. With neither side able to gain the advantage, a congress was held at Arras in north-eastern France, in the summer of 1435. Though no agreement could be reached over either the Crown of France or the extent of the English territories, the congress was the scene of one important development, namely the decision of Philip, duke of Burgundy, to abandon his support for Henry VI. Much of Upper Normandy fell to the French in 1435-6, including the important ports of Dieppe and Harfleur, and in 1436 they also took Paris. The English did not attempt to retake the capital, but concentrated on regaining Upper Normandy and defending their other holdings in northern France. A further attempt to reach a diplomatic solution, at a meeting near Calais in 1439, met with failure, but in 1444 a truce was agreed. It was arranged that Henry VI would marry Margaret of Anjou, a descendant of King John II and niece by marriage of Charles VII. Henry was eager to make peace, and in 1445 he secretly agreed to give up Maine to the French. His own men were unhappy at this arrangement, and though Matthew Gough was ordered to surrender Maine in 1447 he did not do so until 1448. French forces invaded Normandy in 1449 and found the garrisons too weak to resist. The English were defeated at Formigny in April 1450, a battle in which Matthew Gough’s life was saved by William Herbert. In August 1450, Cherbourg, the last of the English strongholds in Normandy, surrendered to the French. The English had lost all their holdings in northern France with the exception of Calais. Then in 1451 the French captured most of Gascony, including Bordeaux. The following year the English managed to regain control of Bordeaux, but the French defeated them at Castillon on 17 July, 1453, and killed their commander, John Talbot, earl of Shrewsbury (father of John Talbot, the second earl). The Hundred Years’ War was effectively over, the English having lost all their French lands save for Calais, but this did not lead to a lasting peace. Henry VI’s mental state deteriorated and his weakness, combined with dissent and rivalry amongst the nobility and wider unrest following the defeat in France, would soon lead to fighting over the Crown of England itself (see the Wars of the Roses). >>>Welsh soldiers |

Unless otherwise noted, copyright on the content of this website belongs to the University of Wales